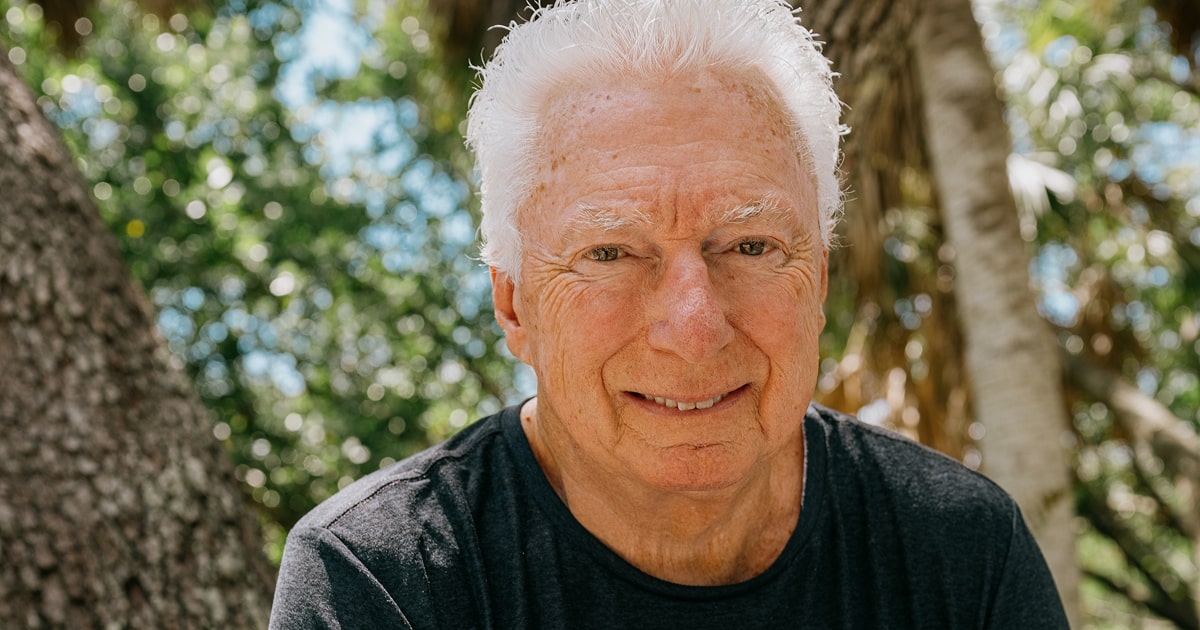

AG Lafley on leading with simplicity

The two-time former CEO of P&G, AG Lafley is regarded as one of the most successful business leaders of his era, handling growth and streamlining with equal skill.

Business Leaders rarely get a repeat performance at the same company. Not so for AG Lafley. Under his first 10 years of direction, he doubled sales and then tripled profits for the US consumer products behemoth Procter & Gamble, making it one of the 10 most valuable companies in the world. Then, after a three-year break, he came back for a second stint at the helm and used his skills to adapt P&G for a new age, streamlining the company and setting simplicity to work under a very clear set of principles while also pushing innovation. Now in a more relaxed phase of his life, he can look back and reflect on these two very different periods of management and the challenges that came with them. He spoke to Think:Act Magazine via video link from Sarasota, Florida, and reflected on everything from the importance of R&D to why we need human empathy in an AI age.

AG Lafley

is a CEO, business mentor, non-profit leader and philanthropist who served two stints as CEO of Procter & Gamble, first from 2000 to 2010 and then again from 2013 to 2015. He is also the author of several Harvard Business Review articles on strategy, innovation and leadership as well as the co-author of the bestselling books Playing to Win and The Game-Changer.

Today, Lafley consults on business and innovation strategy, advises on CEO succession and coaches experienced, new, and potential CEOs. He currently serves as the founding CEO of The Bay Park Conservancy in Sarasota, Florida.

How did you think through the strategy and develop principles that would hold well across the P&G organization, brands and countries?

The first principle for me has always been “the consumer is the boss”: The purpose of any business is to create a customer, serve that customer better than anyone else can and keep that customer for as long as you can. Classic Peter Drucker. The second principle was, if we were going to win, we had to choose where we were going to play. The first question about where to play is “who”; consumers who believed that our brands and products were relevant, important and preferred them to the other choices that they had. So we focused on winning the first moment of truth when the consumer shopped in whatever retail or e-commerce environment. We focused on winning the second moment of truth when the consumer used our product at home: Did we perform and create a great experience? If we won those two moments of truth, then we had to do it all over again. That was our simple principle. Focus on the consumer, offer them innovative brands and products that met their needs.

How should leaders think long-term, build for the future and also handle the quarter-on-quarter culture that has gripped most corporates?

We were very clear from the outset that we were focused on the longer term, five to 10 years. You have to be clear that’s your mindset, how you’re going to lead, manage and operate your businesses. We were not in any businesses that were on a quarterly cycle: two-, three-, five-year cycles. The capital-intensive businesses were on five- to seven-year cycles. Since we were a public company headquartered in the US, we had to report our financials on a quarterly basis. We focused on the year and it was just the next milestone in our journey along the way to the decade.

There would be volatility quarter by quarter. But we asked our investors, employees, customers and suppliers to keep their eye on where we’re headed year by year. In the end, the market and investors are looking at how consistent, reliable and sustainable your business and financial results are. If your organization can deliver that level of consistency, reliability and sustainability, then in general, they don’t get too excited by quarters.

In between both your P&G stints, you worked in private equity and in venture Capital. How did these industries shape your perspective?

I’m an oversimplifier. If you step back, there are three kinds of businesses: “start them up” businesses (i.e. startups), “fix them up” businesses (private equity) and “keep them up” businesses (like P&G, where you have to be able to do startups, fix-ups and be able to sustain). “Fix them up” businesses teach you cash discipline. Most businesses perform better if they have their balance sheet in order, they have cash discipline – and they have their cost structure where they want it. In general, you don’t want to be investing a lot of money in new innovation or new acquisitions unless and until you’ve got your balance sheet and cost structure right.

Private equity is pretty much 90-100% focused on value creation. Their time horizon is three to five, maybe seven years. So it’s a different time horizon than P&G, but it’s long enough for the leadership and the strategy, the choices you choose to make a difference on the operating results.

How should CEOs today aspire for simplicity when the contexts we operate in are so complex?

Every generation of CEOs thinks they are in the most complex, tumultuous and difficult environment. So I thought back on my two tours in Asia and the Asian financial crisis, where an Indonesian business worth $100 million went to $18 million in revenue overnight. I lived and worked through the Kobe earthquake as well as the tsunami in Southeast Asia. 2000 was a tumultuous year, and in 2002 we had the dot-com bubble and in 2008-09 we had the global financial crisis and the worldwide recession. Things are tough right now and there is complexity, uncertainty and volatility. But that’s part of the job.

The more complex, volatile and uncertain things get outside, the simpler you have to make things inside. That means a few simple goals on the strategy side that clearly define what is winning for your company – and a few simple choices about where you are going to play and how you’re going to win as well as what core competencies you need.

“The purpose of any business is to create a customer, serve that customer better than anyone else can and keep that customer for as long as you can.”

Things need to be very simple on the operating side as well. We simplified in a bunch of ways: I only focused on four encounters with the president, CEOs, category and country leaders. I threw out the notebook and said, I want to talk about two to three questions: Are you winning? If you’re winning, how are we going to widen the moat? If you’re not winning, what one or two strategic choices do we need to make to get you on the path to winning?

I would go through their innovation strategies and programs, then. I threw out the notebook and wanted to see the product prototypes, technologies and consumers’ reactions to them. I sat down with them once a year and looked at their succession planning and talent pipeline. Lastly, I went through the annual rolling one- and two-year plans. Again, I didn’t want to see the notebook or the PowerPoint. I just wanted to see the numbers and the two or three things they were going to do in their operating plan to deliver their strategy.

So not getting caught up in all the concerns that are swirling around outside and staying focused on the few things that you can control and influence really make a difference to your consumer and to value creation for your company.

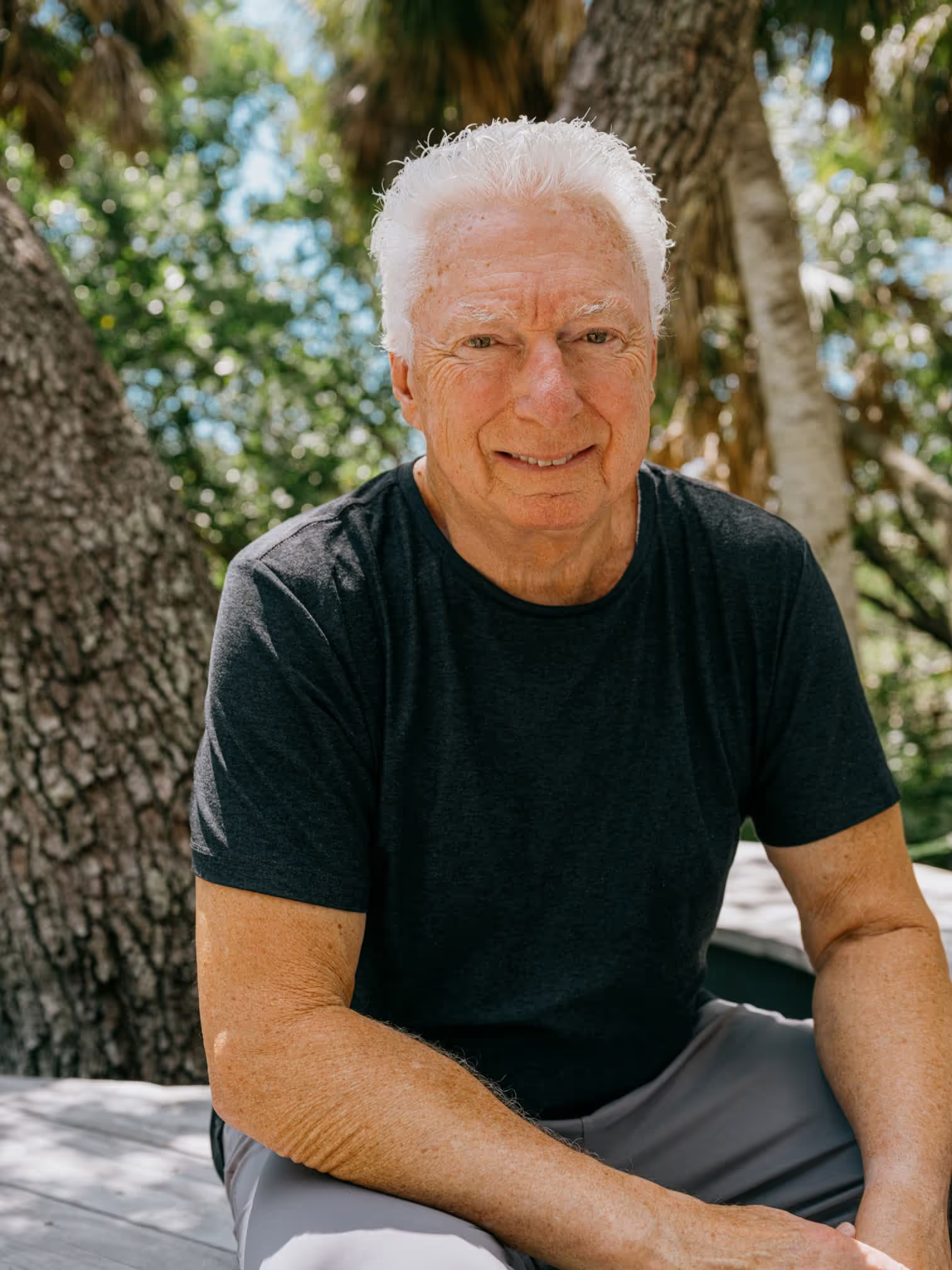

“BAY” WATCH

Under AG Lafley’s watchful leadership, The Bay opened its first 10-acre phase in October 2022 and is currently expecting to open its 14-acre second phase in 2026. The completed park will cost around $200 million and take another eight to 10 years to complete over four or more phases.

“We spent more on R&D than our next five competitors combined. We were going to win or lose on innovation.”

Did you also manage to cascade down this way of working across the board?

We tried very hard to do so because we wanted the strategy work at the country level to be done in the country. We did a whole bunch of different things. When I went to the country, my review with them was as I described: going through strategic objectives, goals, strategy choices, innovations they were bringing to market, their leadership team and talent pool and how they were performing against their operating plan. Two, we created an executive leadership program and a lot of online and in-person courses because we believed that you could teach “playing to win” strategy and leadership. Some of the countries and categories did extremely well. Others struggled and we tried to enable, empower and help them deliver results. If they couldn’t, you changed the leadership or some team members so you can put together the team you need to get the results you want.

On the topic of choosing where to win, how did you decide on which opportunities were worth pursuing and which ones weren’t?

First of all, the only decisions that my relatively small executive team and I made were the “where to play” decisions and “how to win” decisions for the entire corporation: operating on a multi-industry, multi-sector, multi-category and multinational basis. Where to play at that level was largely a portfolio set of decisions: what industries, sectors, categories and countries? The second area we spent a lot of time on was how to win. How do we need to keep evolving our business model so that we can perform better, support the country, category or sector better? We focused on building core capabilities and competencies. We made multibillion dollar investments in understanding consumers and proprietary research techniques, some of which we developed and some of which we acquired. We invested a significant amount of money in innovation. We spent more on R&D than our next five competitors combined. We were going to win or lose on innovation. Lastly, we invested a lot more than most other companies in the hiring, development and growth of our talent and leadership.

You spent an outsized amount of money on different kinds of innovation including open innovation in the form of P&G Connect + Develop. How did you think through it because it was a gamble after all?

We didn’t invest all that money at one time. We took all of our investments in innovation one step at a time, testing and learning as we went along. Connect + Develop was a test and learn opportunity. Our hypothesis was that while we were inventive and one of the top 10 patentors in the US and in many countries around the world, there were a lot of great inventors out there. We wanted access to inventions and technologies that might have application in our industry sectors and categories. If we insourced some of this innovation and inventiveness, we could put P&G’s commercialization capabilities to use.

Back then P&G had 10,000 researchers and engineers in R&D, and they were very concerned that we were outsourcing R&D. But we were insourcing additional “R” (research) so that we could “D” (develop) and commercialize it. Once people understood that, they started working with first-rate scientists from our suppliers, BASF, Novozymes, research universities and research laboratories. They got stimulated. But it was hard to get it started.

A GROUNDED VISION

Whether working from the Chidsey Building, The Bay’s current office location and the former site of Sarasota’s oldest library, or on the 53 acres of city-owned land that will form The Bay’s grounds, Lafley has brought his background in innovation to a landmark civic project aimed at creating “one park for all.”

A lot of open innovation gets shot down within companies due to cultural issues.

It’s a big cultural issue. We tried to encourage them to give it a try, engage in one experiment. We’d put chemists from P&G together with chemists from BASF, and all of a sudden they were creating new polymers that we could use at both companies. It was a win-win for the research scientists. They got a lot of appreciation and recognition.

If a great research scientist was stubborn and they didn’t want anybody in their laboratory except their handpicked lab technicians, we would find ways to inject positive opportunities into their labs. We’d ask them: “Could you test this for us?” It’s hard to turn that down if you’re a scientist. It didn’t work all the time. But when we started the program, about 10% of the new products and improved products that we took to the marketplace had one or more outside co-innovators or partners. By 2005-2006, it was 40-50%.

We benefited from a culture that was strong on ownership, leadership and innovation. That helped, but wasn’t sufficient. Everybody had to try it for themselves to see whether it worked in their case. Some industries, categories, sectors moved quickly and had success so that was a motivator.

At P&G you focused a lot on human empathy. In today’s world of data, AI and analytics, do you think we are at risk of losing the focus on the human aspect of the customer?

There’s clearly a role for collecting the data that’s relevant and important, and understanding it as well as you can. But I also deeply believe there’s a role for human empathetic insight and understanding. I’ve worked with FIGS, a startup that went public. Think of it as the combination of Lululemon and Nike, a health care uniform alternative to scrubs. They use a lot of data. But CEO Trina Spear and her team also invest a lot of time face-to-face in hospitals and health clinics, with the nurses and primary care physicians who are their primary customers, trying to really understand what life is like in a 12-hour shift and how that impacts what they wear and how what they wear has to perform, fit and feel. So I don’t see a way around that.

AI and machine learning could become more of a commodity and less of a competitive advantage, especially at large, sophisticated companies that have relatively unlimited budgets and human resources to throw against this opportunity. They’re going to be competing at the edge of what they can do with databases and AI. The differentiator will be human beings. There’ll be an advantage to the individuals, leaders, people, companies that can discern unarticulated needs and wants.

“AI and machine learning could become more of a commodity and less of a competitive advantage ... The differentiator will be human beings.”

Stay ahead of the curve!

Sign up for our newsletter and let Think:Act bring you up to speed with what's happening today and guide you on what's happening next.