Adapting the multinational company in an age of uncertainty

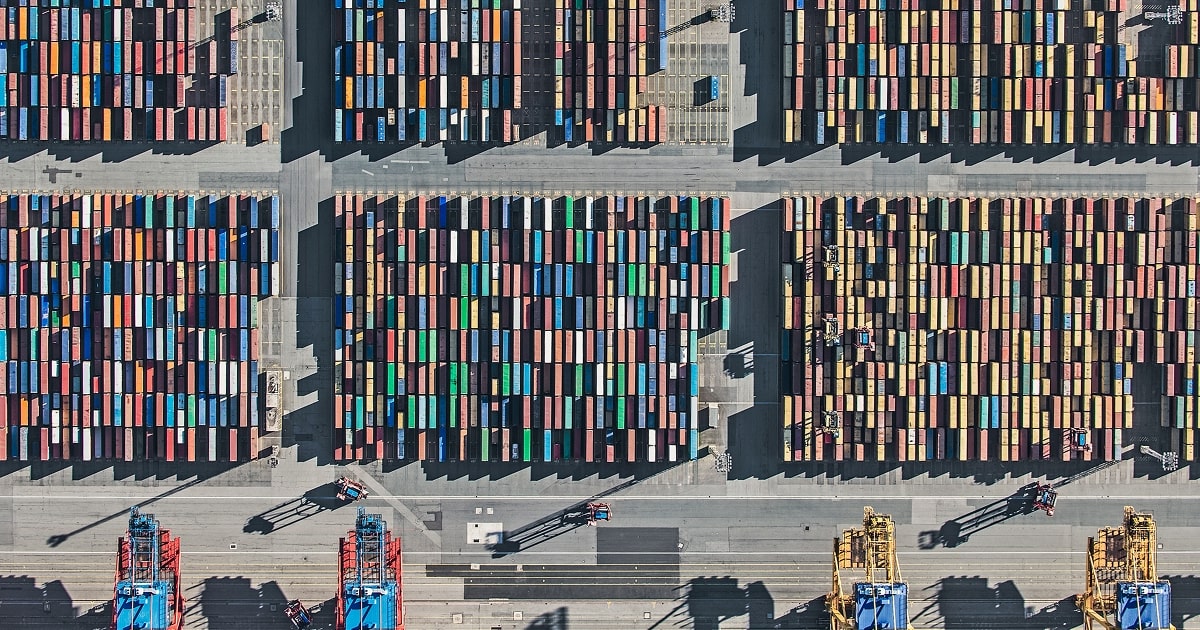

The playbook of global trade is being rewritten, and not for the first time. To maintain their position on the world stage, multinationals must rethink their structures and forge new paths to connect and continue growth across borders.

the aberdeen harbour board, founded in 1136 by King David I of Scotland, can claim to be the oldest surviving company in Britain. But you cannot say it is failing to move with the times. Three years ago, ahead of its impending 900th birthday, it changed its name to the Port of Aberdeen. Companies are indeed a great and, evidently, old idea. Some suggest the word comes from the Latin words con (with) and panis (bread), meaning a company is a place or entity where meals are shared. As empires rose and fell, trade – and companies – grew to be international. What we now call globalization has, in fact, existed in different guises for centuries. So it was a natural development for the multinational company to come into being. This was an embodiment, on a large scale, of Ronald Coase’s “nature of the firm” theory, which was first set out in a paper published by the British economist in 1937 (when the Aberdeen Harbour Board was a mere 800 years old).

Coase’s argument is that firms exist to reduce transaction costs. It can be cheaper to employ people and bring functions or activities in-house rather than constantly going out into the market to buy them. The right size for a firm to be is where transactions costs are still lower than the added costs of managing a larger organization. Markets and consumers are to be found internationally, and so some larger companies became multinational. But are these fundamental and time-honored principles about to change?

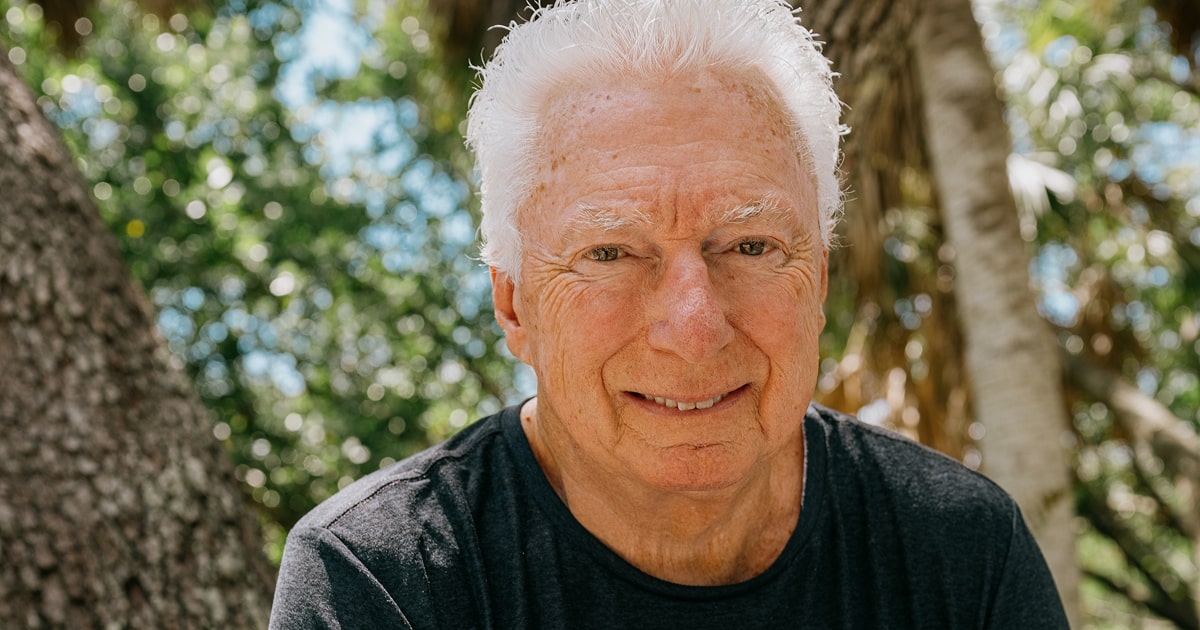

On April 2, 2025, President Trump unveiled his new proposed tariff regime for world trade with the help of some hastily produced charts. This was “Liberation Day,” Trump declared. But business leaders have used other words to describe it: “This is a new Covid moment,” one said at the time. It could mean the end of free trade as we have known it. “The free trade flows until now have been very beneficial,” says Ben Chu, an economics correspondent for the BBC and author of Exile Economics: What Happens if Globalisation Fails? “This uncertainty that Trump’s created is really dampening investment intentions,” Chu adds. “It’s understandable. If you’re a multinational company, are you going to invest in your supply chains when you just don’t know if there will be a tariff or not on what you are bringing in from any given countries?”

After another one of Trump’s many revised tariffs announcements in July 2025, which were set out in a series of letters to world leaders, Justin Wolfers, professor of economics at the University of Michigan, was equally blunt. Each of the tariff letters ended with “these tariffs may be modified, upward or downward, depending on our relationship with your country,” Wolfers noted. “No American company is going to open a new factory based on the protection offered by a tariff which could disappear before the concrete sets,” he said.

Chu agrees with Wolfers. “There is this ‘Trump always chickens out’ [“TACO”] meme or phrase … that may be true in some respects, but if you’re a CEO of a multinational with international supply chains that doesn't help you to make a decision to invest or not,” he says. “He may chicken out or he may not chicken out. Huge uncertainty has been unleashed. And even if the big numbers fall, you’re still at a higher tariff than before.” This all raises fundamental questions concerning structure and strategy for the multinationals of the future. Is “near shoring”/“onshoring” the answer, ducking out of the damage caused by the new tariff regime?

Geopolitics

ASIA RISING: A MORE COMPLEX WORLD

By 2040, China will have surpassed the US to become the world’s biggest economy ($34 trillion vs. $32 trillion). India, at $13 trillion, will be the fourth-largest economy, catching up to the EU (at around $19 trillion). Asia’s total GDP by 2040 will rise to $74 trillion, exceeding the West’s $66 trillion.

Adapted from the Geopolitics toolkit in Think:Act Magazine 47, part of a three-part series offering data insights on geopolitics, technology and organizations.

ASIA RISING: A MORE COMPLEX WORLD

By 2040, China will have surpassed the US to become the world’s biggest economy ($34 trillion vs. $32 trillion). India, at $13 trillion, will be the fourth-largest economy, catching up to the EU (at around $19 trillion). Asia’s total GDP by 2040 will rise to $74 trillion, exceeding the West’s $66 trillion.

Adapted from the Geopolitics toolkit in Think:Act Magazine 47, part of a three-part series offering data insights on geopolitics, technology and organizations.

Choices for corporate leaders are hard and becoming harder. When speed of supply matters as much as security of supply, any friction is bad. Some recent surveys have revealed that companies are prepared to pay a premium for quick delivery although whether security of supply can be reconciled with competitive prices and choice that consumers have become used to remains to be seen.The most powerful example of a successful multinational that has, until now, flourished with existing trade flows is Apple, with its world-beating iPhone. The company’s current CEO, Tim Cook, devised and led the company’s expansion in China, building the powerhouse production of its much-desired goods there. But now Trump is not only threatening major tariffs on all Chinese goods, but an extra 25% on Apple devices made abroad.

The former Financial Times journalist Patrick McGee has described the background to this developing situation in his recent book Apple in China: The Capture of the World’s Greatest Company. In recent years Apple has developed close relationships with Chinese manufacturers and components suppliers, complying with Beijing’s “Made in China 2025” policy. And the Chinese-made iPhone still delivers about half the company’s worldwide revenue. China has made Apple’s phenomenal success possible, but this success has come with strings attached which tie the company firmly to the country.

Apple has shifted some of its manufacturing production to India, but even this has not appeased President Trump. He wants to see a lot more “made in America” stickers on manufactured goods, including those sold by Apple. But why would Apple uproot and relocate the mass of its lower-cost production back to the US, at enormous expense, when the movitations to do so could change with a different president and when the incumbent might yet change his position on tariffs again before the end of his presidential term?

As McGee explained during the course of a recent Financial Times podcast, the Apple CEO has a very narrow set of choices before him. “That’s how Tim Cook must be feeling right now, that he can’t move to India, he can’t diversify outside of China,” McGee said. “He’s totally stuck there. There’s nothing they can really do. That’s Chinese strategy at its finest. And I think they’ve really been outplayed by a long-term thinker. So I want to be able to be more optimistic. I want to believe in American manufacturing, but supply chains take decades and this is the culmination of four decades of Chinese investment.”

How much Apple CEO Tim Cook stated that new tariffs cost the company in Q2 2025, despite a 13.5% rise in iPhone sales attributed to a purchase rush before the tariffs went into effect.

RAISING STAKES

In compliance with EU food safety laws, farms such as Hendrik Dierendonck’s in Veurne, Belgium, raise animals without the use of hormones. The US, which does not have those regulations, is seeking to negotiate for lower tariffs on meat products imported into the EU as part of ongoing trade deals.

“Multinationals are not going away, but it’s clear that substantial barriers are emerging that did not exist before.”

not every multinational is facing Apple’s extreme dilemma – although since it is a dilemma based on the global dominance of its products, it is perhaps not such an awful dilemma to have. Are there some broader principles here that business leaders should be considering as they position their multinationals for the future? Colin Mayer, emeritus professor at Saïd Business School, Oxford, and the head of the British Academy’s extended enquiry into the future of the corporation, feels that this current moment is an opportunity to think afresh about how larger companies are structured and managed. “Multinationals are not going away, but it’s clear that substantial barriers are emerging that did not exist before,” he says. “Part of the problem has been the traditional, highly extractive model, a top-down structure with an HQ located in London or New York, with other activities sited in the lowest-cost places. This has led to quite serious problems in terms of the impacts the business has in different parts of the world. And this is a model that will not work so well in a time of new barriers to trade.”

But Mayer does not look at the onshoring of activities, at great cost and with serious disruption to the business, as a great option either. Rather, he points to the opportunity “to create highly successful, well-resourced local operations which don’t just exist at the whim of HQ but which serve a purpose in the domestic location.” This less extractive model is less vulnerable to the newly emerging tariff-led era, he says. A devolved structure would allow the multinational to delegate authority. “And this is how the best organizations are run,” he adds. “It creates a much more engaged workforce, you have a greater sense and understanding of the role the organization is playing, and more motivated people. It allows for more judicious risk-taking,” Mayer adds. Chu accepts this argument in theory, but while the devolution of decision-making makes sense, “you’ve also got to remember that these are complex multinational systems. They have to function as a whole if you are trying to move goods around the world. The center needs to think about how the system works,” he notes.

A GLOBAL CIRCUIT

Inside Dutch semiconductor company ASML’s headquarters, a machine that helps build the most advanced chips in the world has become a hot topic in negotiations surrounding rising tariffs and political pressures between the EU, the US and China.

Consider Nike, which at the moment makes almost half its footwear in Vietnam, a country that has been hit by new tariffs of (at the time of writing) 20%, reduced from the original 46% which had been threatened. “Vietnam had a great boom on the back of the first Trump trade war, now he's hit them because he’s trying to stop that,” Chu explains. “Nike can’t just say ‘let’s empower our local managers in Vietnam.’ The Oregon operation has to make a decision. Does it move out of Vietnam, does it double down on it and hope it doesn’t materialize … you can’t get away from that challenge,” he says.

While structures do matter, the multinational of the future will be led and managed by people. So the human factor should not be overlooked in this discussion. Lynda Gratton, professor at London Business School, is optimistic that future leaders will rise to the challenge of navigating this changing environment. “The multinational is a very adaptive organization,” she says. “More than any other organizational form it’s the most sophisticated. I think they tend to be better run and better led, simply because the very process of working across countries means that leaders have to confront their norms and expectations and behaviors … multinationals have a structure which is constantly adapting. And it’s adapting to market forces, to regulation, and it’s adapting to the CEO’s perspective.”

Gratton adds that “in a large multinational, one of the issues is around connectivity. How do you connect the different parts of them together? That’s something that any successful multinational will have understood, the idea that work is flowing and moving around the world. Productivity is really on the agenda for a lot of them and generative AI is a way of increasing that. The fundamental topic is work design, and that probably hasn’t had enough attention. What are the tasks they are performing, why are they doing them? That’s a question multinationals do ask themselves.”

Then there is the question of leaders themselves. “When you ask people ‘why will you stay at this company?’ one of the major reasons they stay is that they think they have a future there,” Gratton says. “And when they ask about having a future there, they are looking at the leader and asking: ‘Are they going to be able to navigate through this period? Am I going to be safe here?’ We are getting this new breed of leaders who are running multinationals who came up through managing complex groups, working across different countries. They are very savvy about the world that we live in, and they are very good at narrating a story. Leaders’ stories about the future and what we can expect are becoming very important. Personal agency is going to be very important. An organization becomes a place where you learn. Is this a business I can learn in, build connections, build a network? To help me stay relevant and resilient.”

Two final aspects of this shifting scene are worth considering. First, as Chu points out, digital data keeps flowing, tariff-free, even if physical goods do not. “The amount of data flowing across borders in global capability centers in places like India and Bangladesh … they have been doing a roaring trade,” he says. “They are offering their IT skills as back-office services for multinationals. And they have continued to grow their business through the so-called ‘slowbalization’ era. And it is harder to put a tariff on a multinational sending data between two of its divisions across borders, as opposed to goods. There are people who think that will continue to grow as it’s just so hard to obstruct. Trump is all about goods, he only cares about goods. Maybe this can carry on under the radar and multinationals can continue as they are. Digital trade globalization can continue apace.”

And a final bit of advice for business leaders facing up to this new world? “There is a way for companies to deal with this uncertainty, which is to try and diversify a lot more,” Chu says. “It is better to have your eggs in multiple baskets, even if that adds to your cost. Given the uncertainty about which country is going to be hit by which tariffs it probably makes sense for big companies to spread their production systems around,” Chu adds. “There are better ways of addressing the fragilities than by pulling up the drawbridge. Map your. supply chains, stockpile more and diversify that’s just as true for corporations as it is for governments. You can retain the benefits of being open to global trade as well as making yourself more resilient to some of the shocks that you are exposed to being part of the global system.”

Stay ahead of the curve!

Sign up for our newsletter and let Think:Act bring you up to speed with what's happening today and guide you on what's happening next.