What it really takes to fix a toxic workplace

Companies that prioritize growth at the expense of building a healthy culture risk turning into a toxic stew. Disrespectful, abusive and unethical behavior can sink a brand’s reputation fast if leaders don’t listen to their employees and measure change as it happens.

In 2017, ANNE MORRISS AND HER WIFE, FRANCES FREI, were happily living parallel lives as a married couple: Morriss as the CEO of a biotech company, Frei as a professor at Harvard Business School focused on organizational transformation. Their respective lines of work often overlapped and they often chewed on topics around corporate culture at the dinner table. “And then Uber called,” Morriss recalls. The ride-hailing company was a mess. A high-profile sexual harassment case sprawled across the front pages of newspapers and reports of an aggressive “win at all costs” mentality were creating a public relations nightmare that equated Uber with rampant “bro culture,” shorthand for immature, hypermasculine behavior.

In its crisis, the San Francisco-based company asked Frei to take a leave of absence from Harvard and come in to help clean things up. It was a leap of faith, but Morriss and Frei also saw it could be a powerful testing ground for the ideas around corporate culture they’d spent so long thinking about. Frei’s newly created position at Uber was senior vice president of leadership and strategy and her approach was focused on rebuilding trust.

Uber had compromised its relationship with its employees, and part of Frei’s work was repairing that. It started with rewriting the company’s cultural values, with input from the thousands of employees. Frei also rolled out educational courses for the more than 3,000 managers across the company, teaching them how to communicate better. The founder and CEO Travis Kalanick was ultimately forced to resign following a shareholder revolt, which laid the blame for the ruthless and toxic culture at his feet. By the time Frei left in 2018 and a new CEO, Dara Khosrowshahi, took the helm, the previous challenges had become a thing of the past.

Today, Uber’s catharsis stands as a cautionary tale, not only for Silicon Valley, but many other industries as well. It highlights the dangers of prioritizing growth at the expense of building and nurturing a healthy culture, as well as illustrates how difficult it is to fix an organization from within once toxicity has become the norm.

“it’s all the unwritten rules of work, and most of the rules of work are unwritten.”

COMPANY CULTURE IS AN AMORPHous difficult-to-define phenomenon, but many have tried to pin it down nevertheless. Management theorist Edgar Schein described it as “the learned, shared, tacit assumptions on which people base their daily behavior.” For Morriss, “it’s all the unwritten rules of work, and most of the rules of work are unwritten.” She goes on to explain that “in an example like Uber, it really broke through and it revealed its importance.” And the negative effects are undeniable and manifold: A bad company culture can tamp innovation, lead to high employee turnover and hamper productivity. It can even lead to outright illicit behavior as in the case of US bank Wells Fargo, where employees opened millions of fake accounts under the names of real customers in order to make their sales commissions quotas.

While Morriss was never technically on the Uber payroll, there was a lot of informal collaboration throughout the experience. When the contract with Uber ended in 2018, she and Frei contemplated a return to their previous lives – or to continue their mission to cleanse companies of their toxic culture. The two academics decided to team up and now run a consultancy business working with clients such as WeWork and Riot Games, have written three books and host a podcast for the TED Audio Collective doling out leadership advice.

In their new book, Move Fast & Fix Things: The Trusted Leader’s Guide to Solving Hard Problems, a cornerstone of Frei and Morriss’s advice is centered around the idea of trust. Morriss points to the example of Google. In the early 2010s, Google had become obsessed with a quandary they were facing: Why was it that, despite the fact they were hiring the best people they could get, when they were together on teams, only sometimes would those teams excel – and often they would not. To get to the bottom of the problem, Google started Project Aristotle, a tribute to the Aristotle quote of “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.”

Analyzing reams of data and sifting through the literature, the initiative sought out what made the perfect team. The project came to the conclusion that what mattered was not who was on the team, but how the team worked together and the norms which exist within that group. And the norm that came out on top? “Psychological safety,” Morriss says. The concept of psychological safety was made mainstream by Harvard professor Amy Edmondson and posits that in order to thrive at work, people have to feel like they can speak up, share both ideas and concerns and admit mistakes – all without fear of repercussions.

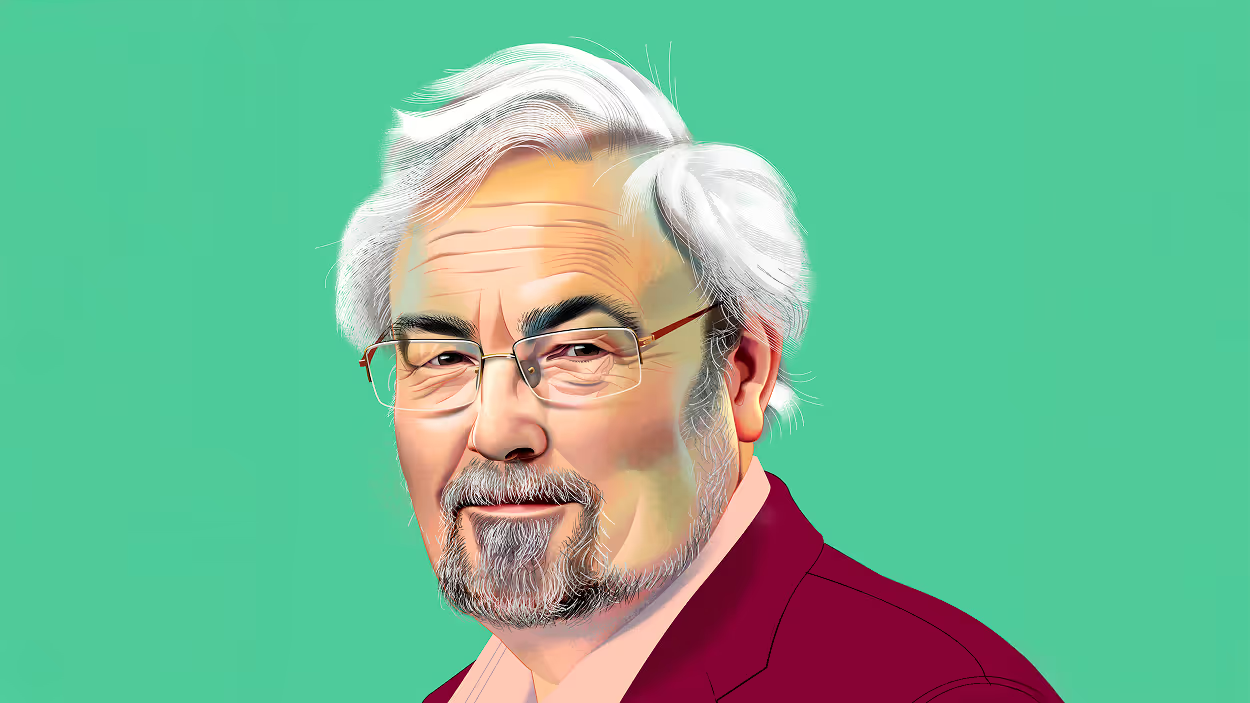

For Charlie Sull, the supposedly amorphous nature of company culture was frustratingly obtuse. In 2020, he teamed up with his father, Donald Sull, a professor of practice at the MIT Sloan School of Management, to found CultureX. The Sulls wanted to take a data-driven approach to finding out what defines a toxic culture. “Pretty early on, we discovered that the biggest bottleneck to effectively managing the culture is effectively measuring a culture,” Sull says – because if you don’t know how to measure it, you won’t know how to fix it. And even if you do enact changes that improve the culture, Sull adds, without accurate data, “you can’t say for sure whether it’s getting better.”

“Pretty early on, we discovered that the biggest bottleneck to effectively managing the culture is effectively measuring a culture.”

“Ask truly excellent leaders what they think about all day and i guarantee you culture is on the top three on their list.”

THE INSIGHT BECAME THE FOUNDATION for a research project called The Culture 500. The father-and-son team analyzed over 1.4 million anonymous employee reviews from more than 500 of the largest employers in the United States posted on the website Glassdoor. They found that when employees mentioned certain features of a company – its agility, whether it had a collaborative nature, pet-friendliness – it would have a small impact up or down on the overall satisfaction reported in their Glassdoor rating between one and five stars. But there was a smattering of topics that, if mentioned negatively, “just completely tank the Glassdoor rating,” Sull explains.

As a result, the Sulls have identified what they call the “Toxic Five” that will doom a company’s culture. They consist of disrespectful behavior, abusive behavior, unethical behavior, cutthroat competition and noninclusive behavior, encompassing both gender and racial discrimination as well as favoritism. If these five shortcomings were mentioned by employees, they could bring reviews down by a full star, Sull says.

They also found in their research that a toxic workplace culture leads to far more staff turnover than bad pay. This became important during the Great Resignation – a cultural movement during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2021 and 2022 when employees were quitting in droves. Employers reacted by hastily creating better cultural atmospheres at their organizations to retain workers, often with mixed results.

Sull notes that now that the job market has shrunk and people are hanging on to their jobs, the appetite to improve culture has dissipated. “It’s cyclical with the labor market,” he says. “When employees are quitting a lot, then the leadership of companies really cares about this issue; they reach out to us about the employee experience to find ways to improve it.” In 2025, though, prioritizing company culture has gone on the backburner for most companies. “We think it is misguided, but that’s the situation right now,” says Sull.

Morriss, however, is more optimistic. Among the organizations that she and Frei work with, roughly half of them are in crisis, such as Uber was. But the other half are just taking big swings, she explains. They appreciate how important culture is and therefore want to be deeply thoughtful about how to evolve it in a way that supports their new strategy. “If you isolate the leaders who are truly excellent and you ask them what they think about all day and what explains the performance of their organization, I guarantee you culture is in the top three on their list,” Morriss says. And this concern is with good reason since a toxic workplace culture can have serious ramifications beyond the internal mood of employees, potentially jeopardizing public trust and irreparably damaging a brand.

TAKE AIRPLANE MANUFACTURER BOEING, which has been put through the public relations wringer for years. Disaster after disaster has torpedoed the brand’s once stellar reputation. In 2024, people across the world were horrified when a fuselage panel covering an unused emergency exit door blew out on a Boeing 737 Max 9 plane mid-flight. It was one more in a long list of incidents, including two crashes in 2018 and 2019 that killed 346 people and the crash of a 787 in 2025 that killed more than 270 people.

Aside from mechanical and quality assurance issues, experts ultimately blamed a weak company culture. They point to the slow and steady shift internally at the company from one focused on innovation and design to one overwhelmingly focused on profit. The change is thought to have started following the entry of executives from another aircraft manufacturer, McDonnell Douglas, in the late 1990s. Since then, the emphasis on financial metrics led to a company culture of fear, documented by internal emails that came to light during various lawsuits and investigations. The concerns of employees went ignored, owing to a lack of trust and transparency in the organization’s culture. As a result, fixing the culture at a company like Boeing isn’t just an HR issue, but a much larger safety issue with implications for the millions of passengers that use their planes.

Channels of open dialogue are paramount to a positive corporate culture, says Neal Hartman, a professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management. “That includes being transparent at many different levels, including the idea that – regardless of your position in the organization – if you see something that you perceive is wrong or not going exactly as it should be, that you are comfortable bringing that up to the appropriate personnel.”

It’s a daunting challenge, as Boeing’s current CEO Kelly Ortberg, who came on board in August 2024 to turn things around, admitted to employees after a good six months in office. “The thing I wish I could change is how we deal with each other,” he said. “We’re very insular. We don’t communicate across boundaries as well. We don’t work with each other as well as we could.” Yet changing the storied company’s culture to make sure employees’ voices are heard would be “brutal to leadership,” he added.

WHAT, THEN, DOES IT TAKE TO TRULY TRANSFORM a toxic work culture beyond leaders announcing they know it needs fixing? Sull boils it down to two big factors: top-team prioritization and knowledge. If you’re a low-level employee embedded in a toxic company culture, then making efforts to change things will be a losing battle. “There’s this whole force of nature going against you,” he says. “Culture is this systemic force that’s affecting everyone.” That’s why change needs to come from the top. “Toxic culture isn’t something that can be fixed from the bottom; it’s not something that can be fixed from the middle. You need the executive team pulling all these different levers for culture in order to have an impact,” according to Sull.

As for knowledge, leaders need hard data on what the culture actually is. “Once you have all those pieces of information, it becomes a lot easier to actually address this problem, and then you can measure it to see if it’s getting better,” Sull says. New AI tools are a welcome innovation since they can take an organization’s pulse much faster, more frequently and more accurately than rote surveys employees dread filling out at regular intervals. A good company culture is often seen as a “nice-to-have,” adds Morriss. But she and Frei view the matter differently, and rather as something essential: “It’s this huge performance variable that will dictate the trajectory of your company. How fast you can go, how quickly you innovate, how much people trust each other.”

Stay ahead of the curve!

Sign up for our newsletter and let Think:Act bring you up to speed with what's happening today and guide you on what's happening next.