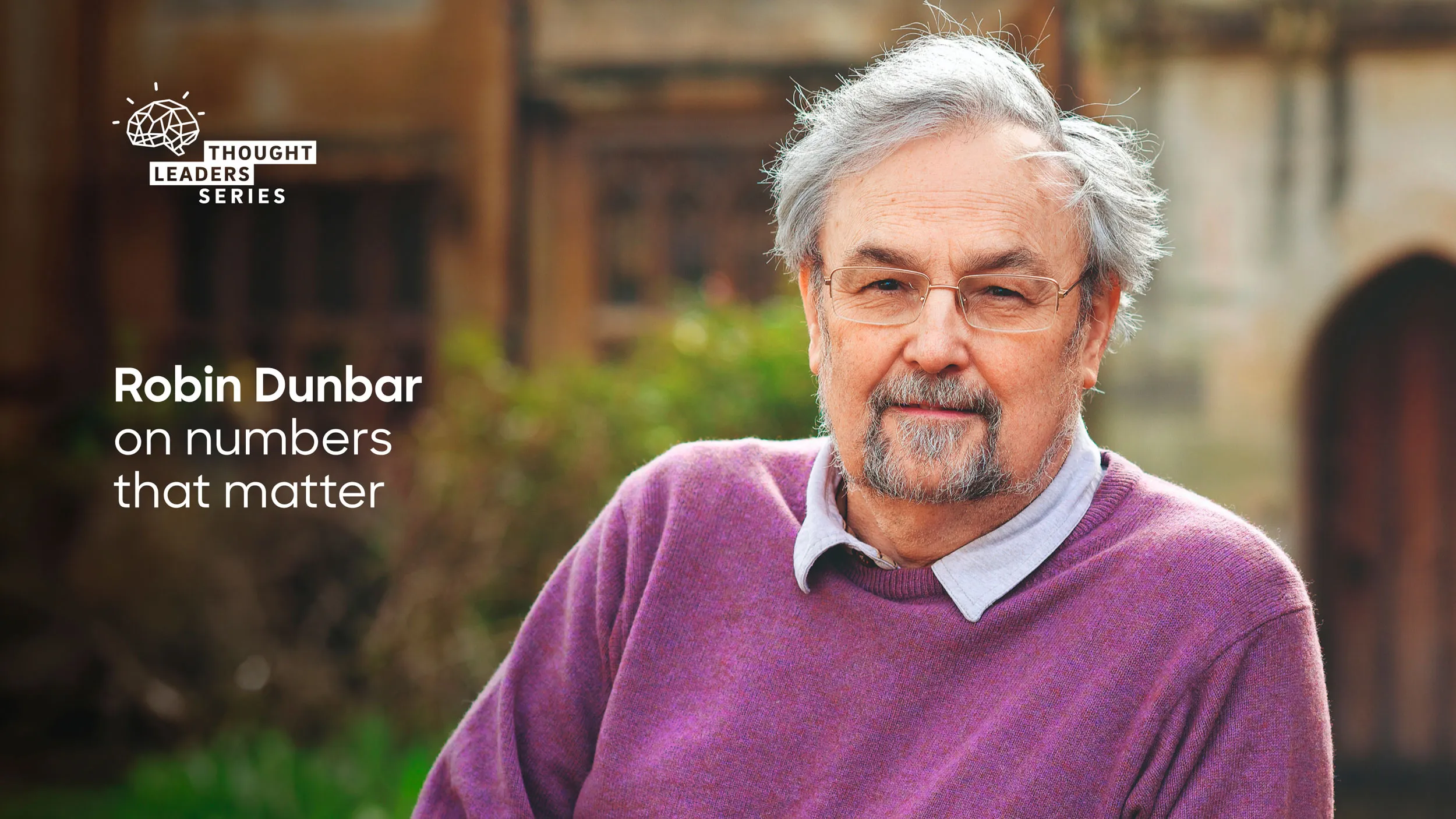

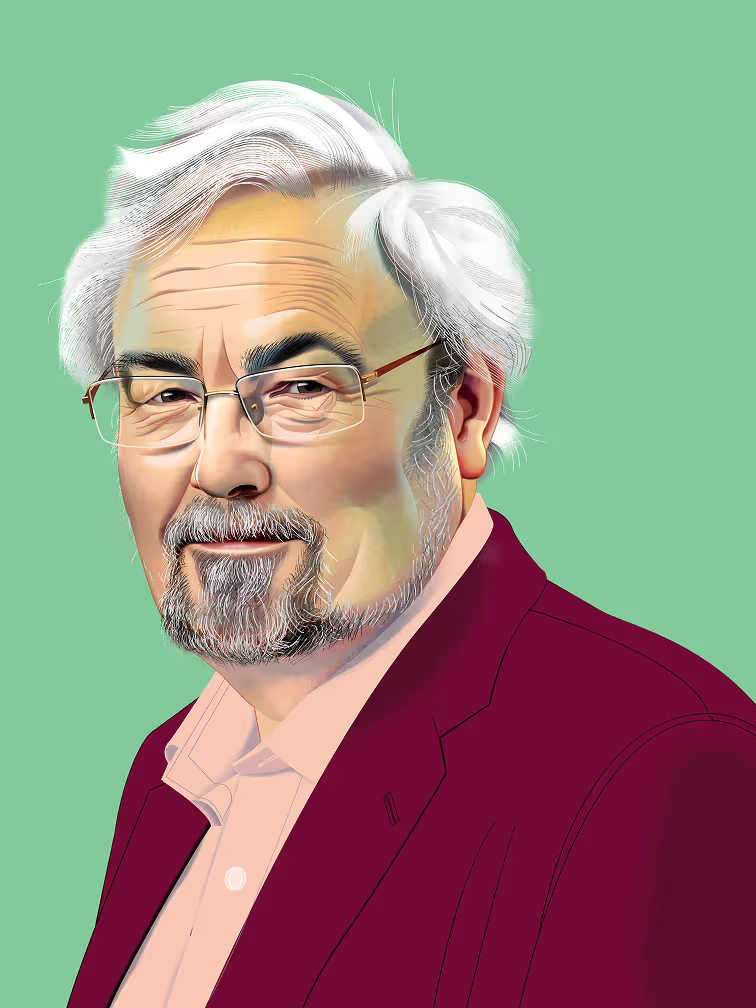

Robin Dunbar on key numbers and group dynamics

Evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar undertook a series of studies on animal societies that shaped how we understand the number of relationships humans can foster. The answer lies in what is known as Dunbar’s Number: 150.

What led you to discover what we know today as Dunbar’s Number?

I was trying to understand why primates spend so much time grooming each other. The general view was that it was for hygiene. I concluded it was for social bonding. The Machiavellian intelligence hypothesis explained why primates have such big brains: They live in complicated societies and they need big computers to deal with all the relationships. To my surprise, we have a relationship between group size and brain size in primates.

I wondered what that predicted for humans, then looked for evidence in hunter-gatherer societies where humans have spent most of our evolutionary history as a species. The natural Stone Age social organizations turned out to be 150. Since then, we’ve been collating data from many different studies, looking for the natural group sizes. In some cases, it’s looking at the world bottom up: your natural social network size, people you know and respect and give obligation to. But also looking top-down: how people are distributed in the environment, i.e. organization size. These two always meet in the middle as 150.

A man of numbers

Robin Dunbar is an evolutionary psychologist and anthropologist specialized in primate behavior, particularly the mechanisms that underpin social bonding. Professor emeritus at the University of Oxford, his most recent books include Friends: Understanding the Power of our Most Important Relationships and The Social Brain. This interview was conducted at the Global Peter Drucker Forum.

You spent six years studying monkeys.

A lot more. In the early 1970s, I studied primates in various parts of Africa, mainly the gelada monkey in Ethiopia, small antelope in Ethiopia and Kenya and feral goats in Scotland for a very long time. Animals provide the groundwork. What humans do is more complicated.

From monkeys to humans, what are some of the similarities you observed in social behavior and constructs?

The things that don’t change are the mechanisms we use for social bonding. How to keep groups together, for example. That’s a problem all smart animals have. If you just have loose and informal arrangements, like a herd, it very easily scatters while feeding and the benefit of being in a group is lost.

If it’s important for your survival and success in life as an animal to have the group stay together, you need mechanisms to counteract these forces. Primates in particular have evolved a number of mechanisms for creating bonded relationships, such as friendships. But by keeping the group together, you increase the stresses: Group members will disagree about different directions to go in the morning when they come down from the trees to go feeding.

What strategies are needed to achieve a balance between group cohesion and such disagreements?

Skills of diplomacy – two of which are very important. One is the capacity to understand the other individual. If somebody kicks sand in your eyes, you understand if it was an accident or not. How you respond depends on the right interpretation. If somebody did it by accident and you beat them up, they are not going to be your friend. Those forces will break up the group. Two is the capacity to inhibit behavior: You resist the temptation to steal somebody’s food because it will break the relationship. These skills are unique to primates.

As the group gets bigger, you get more conflicts with people wanting to do different things. Even if your social world is very limited, it is basically up to 150 people. But, in reality, those 150 people are embedded in much bigger numbers in your village, your town or the organization you work for. These relationships are also dynamic: How well we get on is a consequence of our history up to the present moment, and something happening now might cause us to part company in the future. It’s this capacity to manage this extraordinarily complex world that has made possible what we do as humans and shapes the nature of modern business organizations.

Did the applications of Dunbar’s Number in various fields surprise you?

Yes, it did in some of the places where it appears. But after a little reflection, I’m not surprised because everything we do in life is about human relationships. We live in a village so that we can cooperate and benefit from each other. Modern armies and many organizations have the structure of Dunbar’s Number, even campsites.

Two bot detection algorithms have also been developed – quite separately – and they use my numbers as the basis of identifying human agents on the internet because their connections would look like a Dunbar network. Because bots are not humans, they would have networks that look completely different.

“If it’s important for your survival and success in life as an animal to have the group stay together, you need mechanisms to counteract these forces.”

Facebook vs. face-to-face

Social media might give the illusion that it is now easier to maintain relationships with more people. Keeping acquaintances in view, however, doesn’t make for deeper connections. Even if 1,000 people see what you had for lunch, only 150 will be your functioning network.

To what extent is Dunbar’s Number a determinant of organizational success?

Most of the time it’s not, but it does appear in various places. Wilbert Gore, founder of W.L. Gore & Associates, implemented this. He worked for DuPont, the chemical giant, and felt that big organizations were dysfunctional because silos grew and information didn’t flow.

He found a mathematical formula for the flow of information, and that suggested that units of 150 would work much better. So he insisted that a unit at W.L. Gore & Associates should only be 150, maximum 200 people. As the company grew and they needed more production space, instead of making the factory bigger, they built a new factory, sometimes even next door. That means everybody knows everybody else, so you don’t need a management hierarchy – it’s kind of implicit because you have to have a manager, an accountant, salespeople, people that pull the levers on the factory floor etc., but all these people have the same label: “Gore-Tex Associate.” They know where they stand and the organization is more effective because everybody has a sense of obligation.

When you scale up your unit size to thousands of people, everyone becomes anonymous. In the fractal structure, however, which allows factories to operate as independent units, they make their own decisions. They’re given a strategy by the board but how they implement it is entirely at their discretion. Gore-Tex is often held up as one of the most successful medium-sized companies because of its flat lattice management structure rather than the pyramidal hierarchical structure. It’s based on personal relationships.

Can you order supersized organizations in a way that you don’t lose that sense of community and reduce friction?

There isn’t a golden arrow solution. Our village sizes increased first to town sizes, then to city sizes, then to city states and nation states. Very early on, in hunter-gatherer sizes, the number of people that lived together in the same camp was only about 50. So your community of 150 is split between three campsites, and people can move to another camp if they get fed up with those they’re living with. If you put everybody together into a single village, the stresses arise and you see things coming into play that establish obligations: marital arrangements, charismatic leaders, people you respect or men’s clubs, because the problem is always boys fighting with each other.

“Everything we do in life is about human relationships. We live in a village so that we can cooperate.”

What is the organizational equivalent of these mechanisms?

There are lots of other things that kick in at scale. When you get to village sizes of about 400, doctrinal religions come. In hunter-gatherer societies, religions tend to be a shamanic kind: Shamans go into trance and everybody takes part. Trance states seem to arise because the endorphin system is activated by these activities. There are two ways of getting into trance states: the sledgehammer way, or how the hunter-gatherers do it; and the sophisticated way, which comes out of Buddhism and yoga, where it’s done by breath control. If you go into the edges of trance, the lifting of this sense of belonging and bonding then creates this commitment to the community or a member of the community.

Everything we do in the village in our everyday lives, in building relationships with each other, is endorphin-kicking and creates this sense of community that allows us to transcend the limits of personal relationships: laughing together, singing, dancing, rituals of religion, eating together, telling emotional substories.

We live in a very fluid world: We are born in one place, grow up somewhere else, and go to school, college and work in other places. What implications does this have for the circles we form and those that we can maintain?

It doesn’t seem to have any implications for the sizes of the circles or their emotional content because the circles are based on frequencies of contact and how many people we can manage at a given level of contact for emotional closeness. Our friendships are very dependent on frequency of contact. You have to keep investing, keep seeing them or friendships will decay naturally. Family relationships do the same, but much slower. So what you end up with over the course of your lifetime is little groups of people that you’ve retained. It’s not the whole group you were friends with, just the important ones. These little subgroups of friends reflect your life stories as you move. You still have 150 people, but now the 150 is not homogeneous.

Stay ahead of the curve!

Sign up for our newsletter and let Think:Act bring you up to speed with what's happening today and guide you on what's happening next.